Welcome to Restaurant 4.0 Restaurant

Welcome to Restaurant 4.0 Restaurant

Welcome to Restaurant 4.0 Restaurant

Welcome to Restaurant 4.0 Restaurant

Welcome to Restaurant 4.0 Restaurant

Welcome to Restaurant 4.0 Restaurant

MAIN STREET'S RESTAURANT FOUNDATIONS

Main Street’s earliest restaurants were born from the energy of change. Steam power, mechanized mills, and improved transport networks transformed how food was grown, shipped, and served. Inns and taverns evolved into community dining houses, where travelers and locals gathered not just for meals but for news and debate. The new age of innovation brought iron stoves, glass windows, and printed menus — modest inventions that redefined hospitality and consistency.

For a Climber in today’s restaurant world, this era holds lessons worth studying. Progress didn’t arrive neatly; it came through hard work, adaptation, and courage to experiment with unfamiliar tools. Those early cooks and hosts weren’t waiting for the future — they were building it from fire, sweat, and curiosity.

Social Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Economic Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Cast-iron stoves replaced open hearths, making cooking faster and safer. Families gathered around kitchens more often, blending warmth, conversation, and shared meals.

Economic Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Economic Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Mass-produced iron pots and pans offered even heat distribution. Meals became more consistent, helping taverns and homes serve larger groups with efficiency.

Educational Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Industrial glassmaking enabled affordable dishes and cups. Dining became a display of hospitality, elevating the look and feel of Main Street family meals.

Infrastructure Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Restaurant 1.0

Gear-driven roasting devices freed cooks from manual turning. Restaurants could serve evenly roasted meats faster, fostering public dining as a social event.

OUR THREAD OF TIME - INNOVATIONS TO IMPROVE THE HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Cast-iron stoves replaced open hearths, making cooking faster and safer. Families gathered around kitchens more often, blending warmth, conversation, and shared meals.

Improved Metal Cookware (1760)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Mass-produced iron pots and pans offered even heat distribution. Meals became more consistent, helping taverns and homes serve larger groups with efficiency.

Glassware and Tableware (1770)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Mechanical Spit Roasters (1780)

Industrial glassmaking enabled affordable dishes and cups. Dining became a display of hospitality, elevating the look and feel of Main Street family meals.

Mechanical Spit Roasters (1780)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Mechanical Spit Roasters (1780)

Gear-driven roasting devices freed cooks from manual turning. Restaurants could serve evenly roasted meats faster, fostering public dining as a social event.

Steam-Powered Food Mills (1800)

Gas Lighting in Dining Rooms (1820)

Steam-Powered Food Mills (1800)

Early steam engines powered grain and sugar mills. Consistent flour and sweeteners enabled bakeries and cafés to expand across growing towns.

Canning Experimentation (1810)

Gas Lighting in Dining Rooms (1820)

Steam-Powered Food Mills (1800)

Nicolas Appert’s method of heat-sealing food in jars extended shelf life. Families could preserve harvests; restaurants began offering seasonal dishes year-round.

Gas Lighting in Dining Rooms (1820)

Gas Lighting in Dining Rooms (1820)

Gas Lighting in Dining Rooms (1820)

Gas lamps brightened taverns and eateries. Evening meals became lively community affairs, extending social hours and Main Street nightlife well beyond sunset.

Restaurant 1.0 Online Course

Gas Lighting in Dining Rooms (1820)

Gas Lighting in Dining Rooms (1820)

Gear-driven roasting devices freed cooks from manual turning. Restaurants could serve evenly roasted meats faster, fostering public dining as a social event.

RESTAURANT 1.0 VIRTUAL REALITY WORLDS

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Cast-iron stoves replaced open hearths, making cooking faster and safer. Families gathered around kitchens more often, blending warmth, conversation, and shared meals.

Improved Metal Cookware (1760)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Mass-produced iron pots and pans offered even heat distribution. Meals became more consistent, helping taverns and homes serve larger groups with efficiency.

Glassware and Tableware (1770)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Mechanical Spit Roasters (1780)

Industrial glassmaking enabled affordable dishes and cups. Dining became a display of hospitality, elevating the look and feel of Main Street family meals.

Mechanical Spit Roasters (1780)

Cast-Iron Cooking Revolution (1750)

Mechanical Spit Roasters (1780)

Gear-driven roasting devices freed cooks from manual turning. Restaurants could serve evenly roasted meats faster, fostering public dining as a social event.

MEET BREEZY AI - YOUR RETAIL 4.0 HISTORY GUIDE

MEET BREEZY AI

New technologies began reshaping how Main Street economies functioned — even in restaurants that were still small, family-run, and close to the land. Coal power, steam engines, and improved metal tools transformed food preparation. Simple but revolutionary devices like iron stoves and precision clocks gave cooks greater control over heat and timing, increasing consistency and reducing waste. These changes set the stage for the restaurant as a dependable community anchor rather than a luxury reserved for travelers.

As cities grew around new factories and rail depots, workers needed quick, affordable meals. This sparked the rise of public dining rooms and inns that served steady, repeatable menus built on early industrial logistics — better mills, faster deliveries,

San Diego 4.0 Hotel Tech Stations

San Diego 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

San Diego 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Coal replaced wood for cooking, allowing hotter, longer-lasting fires. It transformed taverns and inns into more efficient, year-round food establishments along Main Streets.

San Diego 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

San Diego 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

San Diego 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

The cast-iron stove centralized heat and control, enabling restaurant owners to prepare multiple dishes simultaneously and standardize cooking temperatures.

Restaurant Tech Stations

San Diego 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Gas Station Tech Stations

Industrial pottery production made uniform dishware affordable. Main Street inns adopted matching plates and cups, elevating presentation and signaling professionalism to guests.

Gas Station Tech Stations

San Diego 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Gas Station Tech Stations

Steam technology improved brewing consistency and scale. Local taverns grew into community anchors, linking nearby farms, tradesmen, and urban Main Streets through steady demand.

REGIONAL RESTAURANT 4.0 HISTORY CAMPAIGNS

San Diego Restaurant 1.0 History

Orange County Restaurant 1.0 History

Orange County Restaurant 1.0 History

Cast-iron stoves concentrated heat, reduced smoke, and allowed restaurants and inns to shrink chimney size, strengthening walls and enabling multi-story kitchen construction downtown.

Orange County Restaurant 1.0 History

Orange County Restaurant 1.0 History

Orange County Restaurant 1.0 History

Durable brick ovens replaced clay hearths, stabilizing interior temperatures, improving bread output, and shaping early restaurant kitchen blueprints along brick-lined Main Streets.

Los Angeles Restaurant 1.0 History

Orange County Restaurant 1.0 History

Los Angeles Restaurant 1.0 History

The first gas-lit dining rooms extended business hours, prompting street-level gas mains, lamp posts, and safer evening infrastructure for growing Main Street corridors.

Main Street Innovators Podcast

Orange County Restaurant 1.0 History

Los Angeles Restaurant 1.0 History

Purpose-built ice houses let restaurateurs store perishables longer, spurring stone-walled outbuildings and the first insulated cellar designs beneath city eateries.

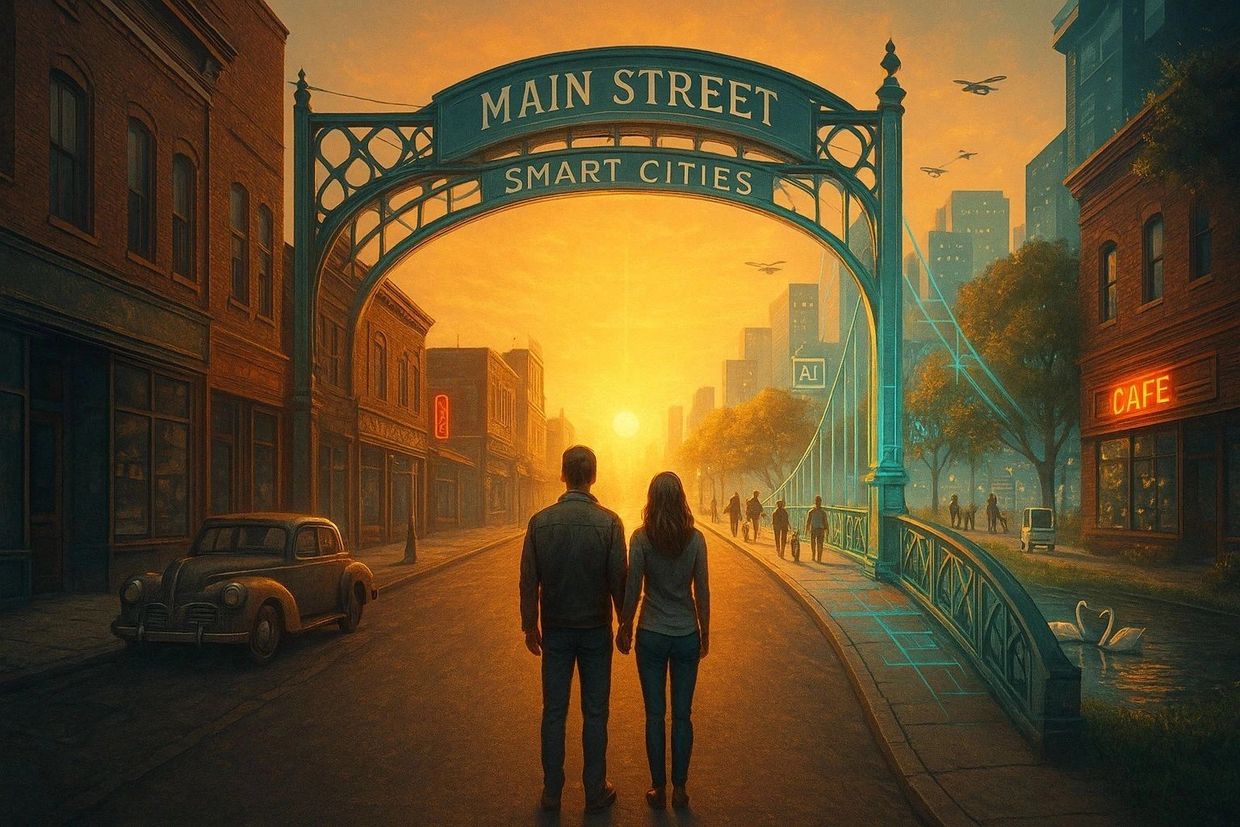

Main Street Smart Cities realigns a city's history with its future. Our mission is to ensure that Main Street continues to lead humanity into the Fourth Industrial Revolution. We believe a new dawn is rising again in America. Our nonpartisan campaigns introduce new technologies to rethink what's possible to move humanity forward.

Copyright © 2025 Main Street Smart Cities

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.